Errors in Machine Learning Benchmark Datasets

Introduction: The importance of dataset quality

It’s interesting that, while the importance of dataset quality is almost axiomatic in the physical sciences, machine learning research has overwhelmingly focused on model improvements rather than dataset improvements. Researchers primarily use performance on existing benchmark datasets as a proxy for model improvements. This is likely because creating a high-quality dataset is a much harder task than training a model. Whole companies, such as Scale AI, exist only to build high-fidelity machine learning datasets. In fact, many of these benchmarks, which are intended to be “gold standard” datasets contain labeling errors (e.g., ImageNet, Amazon Reviews) as shown by Northcutt et al. Importantly, if such issues can plague meticulously curated benchmarks, you can be sure that these types of label errors are even more pervasive in real-world datasets that are used to inform high-stakes decisions in the financial, legal, and healthcare domains.

Understanding and correcting noisy labels in these datasets is key (🔐) to mitigating risk and improving decision making. In this blog, I explore the confident learning approach developed by Northcutt et al., and apply it to the MultiNLI (Multi-Genre Natural Language Inference) dataset. This dataset forms the basis for one of the tasks in the canonical “GLUE” natural language processing benchmark.

Textual entailment and the MultiNLI dataset

Textual entailment is a natural language processing task that involves understanding the logical relationship between two pieces of text called the “premise” and the “hypothesis”. Entailment can be framed as a three-class classification task in which a model attempts to determine if the “hypothesis” can be logically inferred from the “premise,” assigning the two pieces of text to one of three possible labels: contradiction, neutral, and entailment. Examples of each of these labels in the MultiNLI dataset are shown below:

Contradiction

Premise: Your contribution helped make it possible for us to provide our students with a quality education.

Hypothesis: Your contributions were of no help with our students’ education.

Neutral:

Premise: yeah well you’re a student right

Hypothesis: Well you’re a mechanics student right?

Entailment:

Premise: The other name, native well is, as a later explorer David Carnegie, author of Spinifex and Sand (1898), points out, a misnomer.

Hypothesis: The alternative name, resulting from a translation, was a misnomer according to the explorer David Carnegie.

The MultiNLI dataset (which was created at NYU by Williams et al.) contains about 433k such sentence pairs annotated with textual entailment labels. The crowd-labeled pairs are taken from a variety of genres of both spoken and written text.

Confident learning: a method for identifying noisy labels

Confident Learning is a data-centric approach for identifying which data in a dataset has noisy labels (i.e., which data is mislabeled or confusing). The approach was developed at MIT by Northcutt et al.. The intuition behind this approach is that a model’s confidence in its predictions on a held-out set can be used to identify and correct mislabeled data within that held-out set (hence the name confident learning). From a practical standpoint, given a fixed classification ontology, data points identified as having noisy labels can either be relabeled or removed.

Confident learning can also reveal when a classification ontology is not well-structured. Take, for instance, an image classification task that differentiates between two breeds of cows: Ayrshire and Guernsey.

Due to the visual similarities between these breeds, classifying them based on images alone may result in low prediction confidence. Simply discarding these data is likely sub-optimal, however, as the classifier is accurately recognizing the subjects as cows. Here, the issue may lie in the design of the classification ontology itself, and it might be more practical to combine these two categories into a single, broader class, such as ‘brown cow’.

Feel free to skip this next portion if you are not interested in the math, it’s not necessarily important for developing an intuition around the approach. But I like math so here is a little: Confident learning assumes that all datapoints in a labeled dataset, \(X := (x, \tilde{y})\) (where \(\tilde{y}\) is the potentially noisy assigned label), have a latent true label \(y^*\). Confident learning aims to estimate \(p(\tilde{y}, y^*)\), which is the joint distribution between the noisy and true labels. This is by creating a matrix called the confident joint, which is given by:

\[C_{\tilde{y}, y^*}[i][j] := |\hat{X}_{\tilde{y}=i,y^*=j}| \text{ where } \hat{X}_{\tilde{y}=i,y^*=j} := \{ x \in X_{\tilde{y}=i} : \hat{p}(y = j; x, \theta) \geq t_j \}\]where the threshold \(t_j\) is given by

\[t_j = \frac{1}{|\hat{X}_{\tilde{y}=j}|} \sum_{x \in \hat{X}_{\tilde{y}=j}} \hat{p}(\tilde{y} = j; x, \theta)\]Each entry in the confident joint is described by a count of the number of items in the dataset that are labeled as \(\tilde{y}\) and for which the model is confident that the true label is \(y^*\). Items that fall on the diagonal are items that are labeled correctly.

Finetuning a BERT model on the MultiNLI dataset

I link a Colab notebook for running the model training, as well as performing confident learning to identify noisy labels. I performed hyperparameter tuning on the training time in epochs, weight decay, batch size, and learning rate using the Ray Tune hyperparameter tuning package. By default, Ray Tune uses a tree-structured parzen estimator approach, which is a Bayesian optimization method introduced by Bergstra et al.. I identified the optimal training hyperparameters to be training for 1 epoch with a batch size of 64, and a learning rate of 2.88e-05. I still performed training on an A100 to investigate the impact of larger batch sizes, but it is actually possible to train this model on a lower-in-memory GPU like a T4 or V100.

Looking for label errors

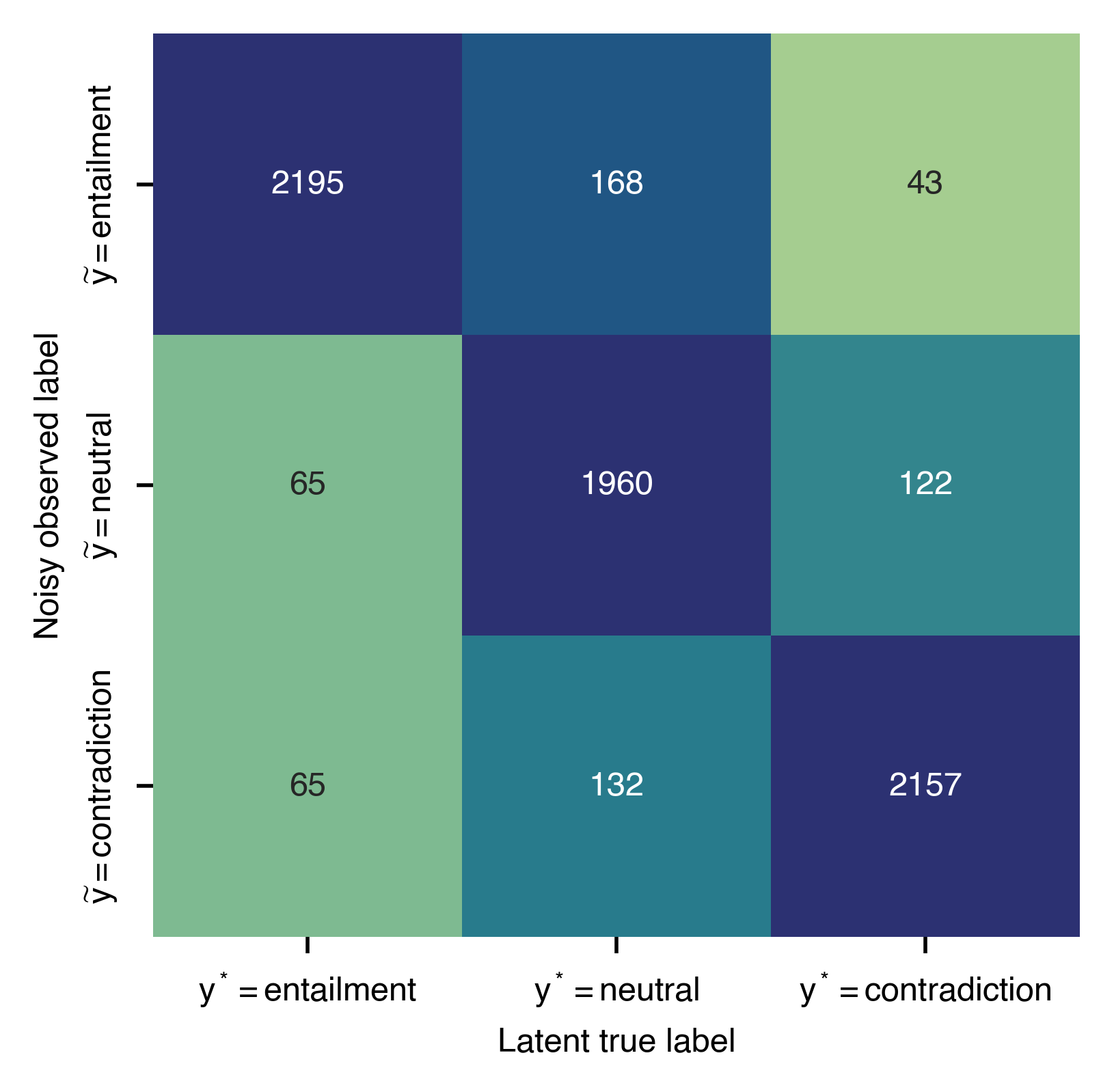

After training a model on the MultiNLI task, I used the confident learning approach to look for label errors in the matched validation set. The confident joint matrix for the matched validation set is shown below.

Of the 9815 entries, 595 were off-diagonal in the confident joint, corresponding to ~6% of all entries. The data suggest that most label noise arises in relation to the neutral class. This is to be expected, as the neutral class bridges the other two classes and is generally the most nebulous of the three. The data suggest that there is some labeler bias away from the contradiction label towards the entailment label, with the entries below the diagonal in the confident joint having more entries than the entries above the diagonal.

Below, I present a selection of cherry-picked off-diagonal entries. Upon a vibes-based manual inspection (extremely rigorous), these entries generally fall into three categories:

- There are indeed many mislabeled data points. This is somewhat expected given the crowd-sourced nature of the dataset, even though there were likely multiple annotators per data point.

- Many off-diagonal entries contain vague or unrelated premises or hypotheses. These are not only more difficult to label but also likely irrelevant to the task.

- Lastly, a significant number of the off-diagonal examples are simply hard! As a result, they are either frequently mislabeled by human annotators or confidently mislabeled by the model.

\(\tilde{y}=entailment, y^*=neutral\)

- Premise: “In the meantime, the philosophy is to seize present-day opportunities in the thriving economy.” Hypothesis: “The philosophy was to seize opportunities when the economy adding lots of jobs.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis does not necessarily follow from the premise. While the premise suggests a general philosophy of seizing opportunities in a thriving economy, the hypothesis narrows this down to a specific time when the economy is adding lots of jobs. This specificity introduces ambiguity, as the premise does not provide information about the economy adding jobs. Therefore, the label of ‘entailment’ is incorrect, and ‘neutral’ is more appropriate as the hypothesis is plausible but not guaranteed by the premise.

- Premise: “It was still night.” Hypothesis: “The sun hadn’t risen yet, for the moon was shining daringly in the sky.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis can be a reasonable inference from the premise, as the presence of the moon in the sky typically indicates that it is still night and the sun has not risen. However, it is also possible for it to be night with no moon (or daytime with a moon), and so a neutral label may be more appropriate.

- Premise: “Anyway, she was found dead this morning.” Hypothesis: “She died during the night but wasn’t found until this morning.” Explanation of label: When she was found does not indicate when she died, although the most likely scenario (considering all possible deaths, which is a bit morose) is that she was found shortly after she died. A neutral label is more appropriate in this scenario.

\(\tilde{y}=entailment, y^*=contradiction\)

- Premise: “It vibrated under his hand.” Hypothesis: “It hummed quietly in his hand.” Explanation of label: Confident learning correctly identfies a mislabel, which arises due to a contradiction in the vibration’s location (i.e., under his hand vs. in his hand).

- Premise: “The Case Study Guidelines” Hypothesis: “Guidelines for the cast study.” Explanation of label: The label error here is due to a likely typo in the hypothesis, where “cast study” should be “case study”. The labeler interpreted the typo, and assigned a entailment label. However, the typo does change the meaning such that the hypothesis does not follow from the premise.

- Premise: “do you really romance” Hypothesis: “Do you really have an affair?” Explanation of label: The premise is not only a sentence fragment but also extremely vague, making it difficult to determine the relationship with the hypothesis.

\(\tilde{y}=neutral, y^*=entailment\)

- Premise: “So, which one of you ladies wants to go first.” Hypothesis: “One of the ladies should go first.” Explanation of label: A mislabeled point where the hypothesis is clearly a reasonable inference from the premise, as the speaker is clearly implying that one of the ladies should go first.

- Premise: “see too much crime on TV and they think it’s way to go i don’t know what do you think” Hypothesis: “They watch too much television.” Explanation of label: Here the hypothesis can be inferred from the premise, as the premise suggests that the subjects are influenced by the amount of crime they see on TV, which in turn implies they watch a lot of television. However, it is somewhat vague, as it is possible they were seeing too much crime on TV but not a large total volume of TV.

- Premise: “We also have found that leading organizations strive to ensure that their core processes efficiently and effectively support mission - related outcomes.” Hypothesis: “Leading organizations want to be sure their processes are successful.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis is a reasonable inference from the premise, as the premise states that leading organizations aim for their core processes to efficiently and effectively support mission-related outcomes, which can be interpreted as wanting their processes to be successful.

\(\tilde{y}=neutral, y^*=contradiction\)

- Premise: “i don’t know if you have a place there called uh or you probably have something similar we call it Service Merchandise” Hypothesis: “You probably have nothing like it.” Explanation of label: A clearly mislabeled point. The hypothesis directly contradicts the premise, which implies that a similar place exists, by saying “You have nothing like it”.

- Premise: “Does anyone know what happened to chaos?” Hypothesis: “I know what happened to chaos.” Explanation of label: This is an interesting example, as the hypothesis seems to directly answer the question posed in the premise, which suggests that the speaker would know what happened to ‘chaos’, which would indicate entailment. However, the premise could also be posed as a genuine question, which would then indicate that the hypothesis is a contradiction, as predicted by the model. Ultimately, it is a somewhat ill-posed problem in this case.

- Premise: “facilitate suits for benefits by using the State and Federal courts and the independent bar on which those courts depend for the proper performance of their duties and responsibilities.” Hypothesis: “The State and Federal courts are the same regardless of location.” Explanation of label: The premise emphasizes the fact that the State and Federal courts have independent bars. The hypothesis directly contradicts this by claiming the courts are uniform with respect to location.

\(\tilde{y}=contradiction, y^*=entailment\)

- Premise: “Without the discount, nobody would buy the stock.” Hypothesis: “Nobody would buy the stock if there was a discount.” Explanation of label: This is an interesing case because the given label is correct, and the predicted confident label is wrong. The hypothesis clearly contradicts the premise by suggesting that a discount would deter buyers, whereas the premise states that the absence of a discount would deter buyers.

- Premise: “NHTSA concluded that while section 330 superseded the section 32902 criteria, it did not supersede the section 32902 mandate that there be CAFE standards for model year 1998.” Hypothesis: “NHTSA concluded that section 330 did not supersede the section 32902 mandate that there be CAFE standards for model year 1998.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis is a direct restatement of a part of the premise, specifically the conclusion drawn by NHTSA regarding the non-supersession of the section 32902 mandate by section 330. Therefore, the label of ‘entailment’ is appropriate as the hypothesis is explicitly supported by the premise.

- Premise: “We are concerned that the significant emissions reductions are required too quickly.” Hypothesis: “We’re concerned about emissions reducing too quickly.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis is a paraphrase of the premise, expressing the same concern about the rapid pace of emissions reductions. Therefore, the label of ‘contradiction’ is incorrect, and ‘entailment’ would be more appropriate as the hypothesis is essentially a rewording of the premise and does not introduce any new information or contradiction.

\(\tilde{y}=contradiction, y^*=neutral\)

- Premise: “Mr. Erlenborn attended undergraduate courses at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana University, the University of Illinois, and Loyala University of Chicago.” Hypothesis: “Mr. Erlenborn earned all of his undergraduate credits at the University of Notre Dame.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis suggests that Mr. Erlenborn completed his entire undergraduate education at the University of Notre Dame, which appears to contradict the premise that lists multiple universities where Mr. Erlenborn attended courses. However, neutral is more appropriate, as it may be possible that he attended but did not complete the classes at the other institutions.

- Premise: “At the same moment I felt a terrific blow on the back of my head She shuddered.” Hypothesis: “I was hit on by a nerdy guy at the local bar.” Explanation of label: The premise and the hypothesis are almost completely orthogonal here. Unless the nerdy guy is somehow adjacent to the blow on the back of the head, I can’t see how this is possibly a contradiction or an entailment. The neutral label seems most appropriate.

- Premise: “Another thing those early French and Dutch settlers agreed upon was that their island should be free of levies on any imported goods.” Hypothesis: “The French settlers did not mind income taxes at all.” Explanation of label: The hypothesis states that the settlers were indifferent to income taxes, while the premies only discusses an agreement to avoid levies on imported goods. These are different kinds of taxes! Therefore, neutral would be the correct label.

Final thoughts

I like confident learning! My assessment is that the primary benefits of confident learning are that it’s model agnostic and it works. I wonder if there is a way to incorporate uncertainty estimates in situations where they are available (neural network dropout, deep evidential classification). There is a whole company built around algorithmic datacleaning methods (with confident learning seeming to be one of the core offerings) now called Cleanlab. Cool stuff!